Some people were inspired to travel by atlases. Some people, by maps. But for some, nothing gave them the travel bug like the adventures of Tintin.

The Adventures of Tintin, a series of adventure comics created from 1929 to 1976, became increasingly popular throughout the 20th century. Its creator Hergé (Georges Prosper Remi), is still a subject of intrigue in the press and among Tintinologists. These adventures address colonialism, the rise of the USSR, organized crime, capitalism, international drug trade, a prelude to World War II (though the war itself is absent), alcoholism, racism, coups d’états, might of multinational corporations, the Cold War and arms race, space travel, modern slave trade, the fight for control of oil and commercial air travel. Recent work in popular geopolitics has pioneered these comics as a source of material in critical geography. These overlapping trends amount to different facets of a single discourse, which places European ideologies at place center of its worldview.

As a young artist, Hergé was influenced by his mentors, specifically Abbé (abbot) Norbert Wallez. Abbé Wallez was a Belgian priest and journalist who was the editor of the conservative Roman Catholic newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century), whose youth supplement Le Petit Vingtième (The Little Twentieth) first serialized The Adventures of Tintin. He encouraged Hergé to use Tintin as a tool for Catholic propaganda to influence Belgian children. This is evident in his earlier works, which are replete with stereotypes from the European right-wing imagination. A breakthrough came in 1934 when the cartoonist was introduced to Zhang Chongren, a Chinese student. Zhang explained Chinese politics, culture, language, art, and philosophy to Hergé, which he used significantly in his fifth album, The Blue Lotus. From this point onwards, Hergé developed ideologically amid the collapse of his native Belgium during World War II. So did the series, becoming more progressive and universalist until the final book, by which time Hergé had developed a certain amount of cynicism. However, racist, anti-Semitic tropes continued to enter his oeuvre. As they got translated into many languages and became available across the globe, charges of political and visual mistakes increased, and many of these albums were extensively reworked—from the text, sometimes even to picture frames.

The first Tintin album, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, was crafted on the orders of Hergé’s superiors to be anti-Soviet propaganda. In this story, appearing a decade after the October Revolution, Hergé denounced Soviet propaganda and the communist system for generating poverty, famine, and terror. This anti-totalitarian theme of the first album would persist throughout the series.

Hergé wanted the second book to take place in the United States of America, a country that fascinated him. However, Abbé Wallez, who distrusted the USA as a land of Protestantism, liberalism, easy money, and gangsters, disagreed. Instead, he asked Hergé to draw a book about the Belgian Congo, which needed white workers.

Tintin in the Congo is a colonial rant, essentially reflecting the dominant Belgian attitude towards colonialism. Published in 1930, it shows an arrogant Tintin gallivanting around the colony, chasing gangsters and dispensing his patronizing white man’s wisdom to stupid and lazy monkey-like natives. Tintin’s bloodthirsty attitude to wildlife in this album is also astonishing. Libraries and booksellers in several countries around the world have removed this book from children’s sections. The strongest argument against its broad availability is probably not that the reader will promote racism but will provoke feelings of inferiority among children of African descent.

Tintin in America represents a significant change in tone. Like the previous ones, this story is hugely caricatured, with Hergé portraying America as the land of Al Capone, cowboys, and gigantism. In his next adventure, Hergé could finally send Tintin to the USA. However, he took to the defence of America’s First Nationals, blacks, and blue-collar workers, while criticizing lynching, theft of native land, and American greed.

The fifth album of the series, The Blue Lotus, is set in China. It criticizes the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and shows with great disapproval Westerners are making racist or ignorant remarks about the Chinese. Hergé was very concerned with accurately portraying the country, and the adventure has anti-imperialist tones.

The Broken Ear is set in the fictional South American republic of San Theodoros and takes a critical view of Western business people conspiring to provoke war over what they think will be profitable oil fields. They use bribery, corruption, and the sale of arms to both sides to start a conflict, much like the Mukden Incident in The Blue Lotus. The war over the Gran Chapo oil plains is based on the Chaco War of the early 1930s. According to the classic barbarian stereotype, the story depicts the Shuar indigenous people, famous for their tsantsas (“shrunken heads”).

The Black Island is, in contrast, a straightforward thriller, with Tintin in pursuit of money forgers, with the chase to Scotland giving it a feel of Alfred Hitchcock’s movie version of The Thirty-Nine Steps. In this album, though Dr. Müller is a German villain and could be read as a parody of the Nazis, the head of the criminal gang, Puschov, is an anti-Semitic caricature.

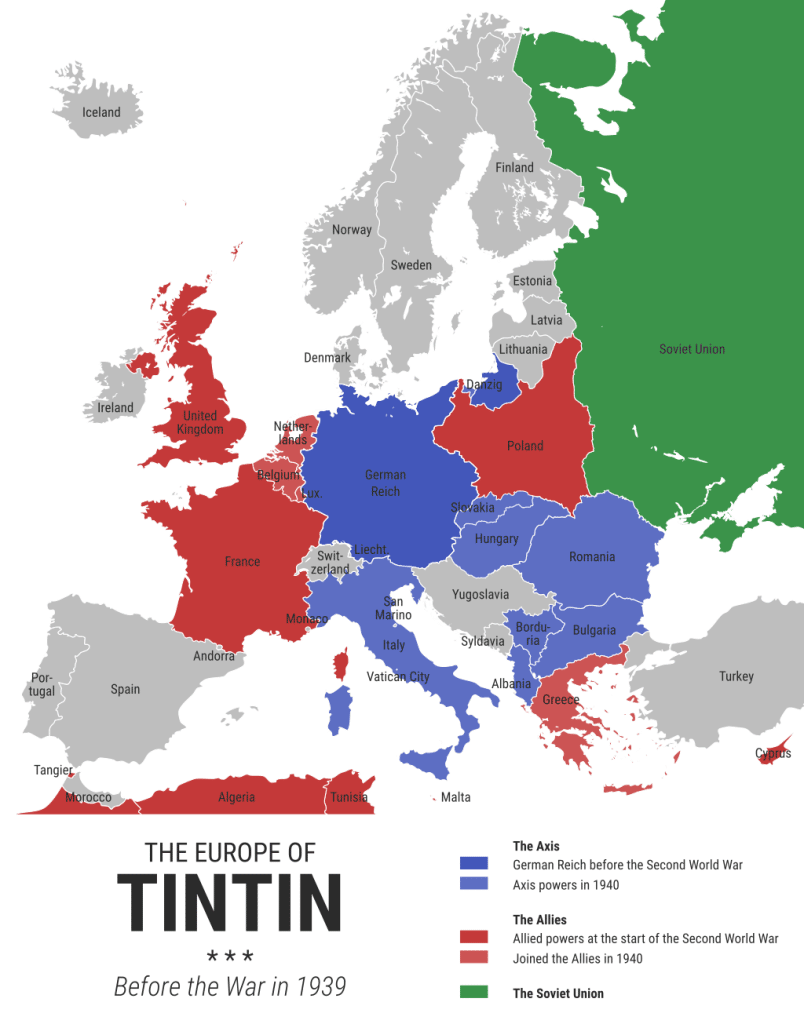

The impending menace of WW II influenced several stories following The Black Island, then by the war itself and the Nazi occupation of Belgium. Even though Hergé favored Belgium’s neutrality, King Ottokar’s Sceptre can be read as anti-Nazi. In this adventure, Müsstler (a possible contraction of Mussolini and Hitler) is the leader of a conspiracy that seeks to merge the kingdom of Syldavia with its old enemy Borduria. Written in 1938, this story reflects the annexation and invasion of neighboring states by Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.

The early and unfinished version of Land of Black Gold (1939-1940) alluded to the mobilization of Nazi war power. This unfinished adventure was set in the British Mandate of Palestine, with British soldiers and officials. The beginning of the war and the defeat of Belgium prevented Hergé from finishing this version. He rewrote it in 1950, setting it in the fictional Arab Kingdom of Khemed, replacing the conflict between Arabs and Jews with a civil dispute between two Arab factions.

During WW II, Hergé worked for Le Soir (The Evening), a newspaper that collaborated with the German occupiers. To avoid controversy during the Nazi occupation of Belgium, Tintin’s stories from this time focused mainly on non-political issues such as drug smuggling (The Crab with the Golden Claws), intrigue, and treasure hunts (The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure) and a mysterious curse (The Seven Crystal Balls).

One somewhat controversial adventure from this time was The Shooting Star, about a race between two crews trying to reach a meteorite that had landed in the Arctic. Hergé chose the subject of this album to be as fantastic as possible to avoid trouble from the censors. However, he couldn’t prevent the intrusion of politics when he made Tintin join a crew composed of Europeans from Axis or neutral countries while their underhanded rivals were Americans. In this adventure, Tintin also flies in a German plane (Arado Ar 196). What was damaging for Hergé was that collaborationist Le Soir published these stories. After the war, he and other members of the newspaper’s staff faced lengthy investigations into their wartime allegiances. The banker and oil magnate funding the American effort to lay a stake on the meteorite—originally named Blumenstein, later converted to Bohlwinkel—depicted with a bulbous nose (much like the recurring arch-villain Roberto Rastapopulos) also led to charges of anti-Semitism.

The post-war Tintin stories are less controversial and develop several recurring themes. Humanism and anti-racism are salient in The Castafiore Emerald. The Calculus Affair is anti-Stalinist but also depicts the lengths to which both sides of the Cold War acquired weapons of mass destruction. The Red Sea Sharks’ theme is international trafficking and slavery, and Hergé has been criticized for his depiction of black victims in this album. In the first edition, they speak pidgin French and seem rather simple-minded. He rewrote their dialogue in later editions. The arms trade is the main topic of Flight 714 to Sydney, in which millionaire Laszlo Carreidas is based on French aircraft industrialist Marcel Dassault. As Dassault was born Jewish, this album is considered anti-Semitic by some.

The last finished album, Tintin and the Picaros, has left- and right-wing undertones. In it, Tintin goes through profound changes. For the first time, he seems made of flesh and blood and perhaps even has weaknesses. For instance, he is at first uncharacteristically unwilling to travel to San Theodoros, where his friends are accused of war crimes based on false charges. In the end, however, he intervenes dramatically, leading to a revolution. But there are no good guys in the political background here: General Alcazar is financed by an international conglomerate, while para-Stalinists of Borduria back his rival General Tapioca. In the last panel of this album, Hergé shows police patrolling the slums. The inhabitants are no better or worse than before the coup d’etat, indicating that all that has changed are uniforms and names on political placards.

The sheer scale of the geopolitical themes addressed in the 24 completed albums makes The Adventures of Tintin a compelling masterpiece chronicle of the 20th century. What I find most fascinating is that while reading the entire series today, one can discern how the themes and values evolve through the adventures, in line with the world politics of the time.